Committee: Consider Raising Key Biscayne’s Debt Cap

Tony WintonJuly 29, 2019

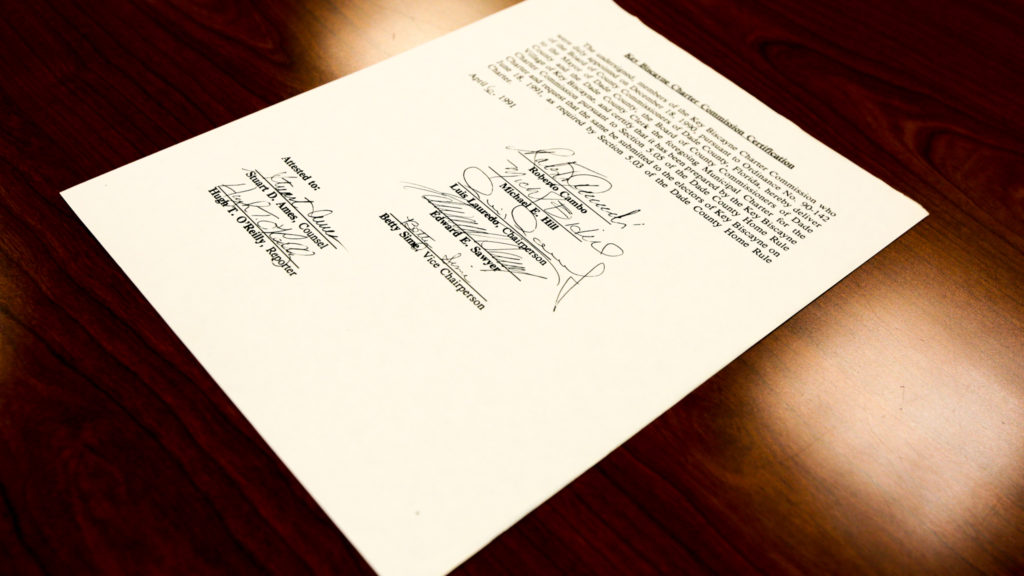

In this file photo, the April 1991 document certifying the intial Key Biscayne Village Charter is displayed at the Clerk’s office, July 26, 2019 (Key News/Tony Winton)

Looking at a long list of expensive projects, a Village committee broached the subject of raising the island’s debt cap to allow enough borrowing for resiliency and other projects.

The idea, which is likely to be controversial, came amid a listing of threats facing the island, ranging from hurricanes and sea level rise to sargassum seaweed.

Raising the debt restriction would require changing Key Biscayne’s main governing document, the Village Charter, a step that requires approval by voters.

Some members of the Village’s 2040 Strategic Vision Board said the cap is crippling the municipality from addressing critical needs.

“In order to approach anything for a solution here, it’s going to cost money. Bear Cut Bridge is going to cost us money,” said chair Luis de la Cruz, a former Village Council Member. “Get used to it.”

The borrowing cap, found in Section 4 of the Village Charter, has two components.

The first provision limits overall debt to no more than 1% of the total assessed value of all the property in the Village. The 2019 Miami-Dade Property Appraiser’s estimate placed that value at $8.3 billion, meaning an $83 million ceiling on indebtedness. But in May, Village Manager Andrea Agha said because of previous borrowing, there is only $70 million more to borrow.

That hard number comes up against at least $116 million in possible big-ticket spending, ranging from undergrounding utilities to flood prevention to a $5 million parking garage – and that’s before contemplating ideas to invest in the Rickenbacker Causeway or secure the aging Bear Cut Bridge; or to undertake more robust sea level rise mitigation projects, like more pumping stations.

“We have an extremely low debt cap. That is indisputable,” agreed board member Tom McCormick. “It’s super low.”

Around Miami-Dade County, municipalities have been seeking financial tools for massive spending. In 2017, City of Miami voters approved $400 million in bonds, half of which are earmarked for flooding risk and sea level rise. The City has not yet gone to market for the bonds and is still identifying projects.

In Coral Gables, officials took a different tack, increasing fees. Starting this year, Coral Gables is collecting fees to build a $100 million infrastructure reserve that’s to be available by 2040.

Most municipalities do not have formal debt caps written into their charters. Although general obligation bonds require votes under state law, other borrowing methods do not.

The Village does have a “very good” credit rating. It was rated as “Aa1,” the second-highest rating, by Moody’s in April. The median ranking for U.S. cities is Aa3.