Key Biscayne’s Arctic Connection

Brian Rivera UncapherNovember 15, 2019

Polar Bears and their cubs increasingly have to wait longer periods of time on land due to a warming Arctic. This photo is from early October 2019, and the sea ice where Polar Bears find their prey is still over 300 miles away. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

Soon after the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its new landmark report on sea level rise last month, I travelled to the Arctic to check out global warming’s ground zero for myself. The ominous report, validated by more than 100 of the best scientific minds from 36 countries, made dire predictions for places like Key Biscayne, an island I have called home for the past twenty years and whose fate is increasingly tied to what happens to the sea and land ice in the Arctic. The study confirms that, unlike the Las Vegas slogan, what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic.

Specifically, it finds that, unless policy makers are able to keep global warming under 1.5°C, communities like Key Biscayne are likely to vanish. Moreover, it warns policy makers that an increase of just half a degree over that will destroy life as we presently know it on our planet. In essence, millions of lives hang in the balance with just half a degree of additional warming. And, as if that wasn’t enough, current scientific estimates place us on a path towards warming the world by 3 to 5°C. The only good news is that there is still a very narrow time window (11 years) to turn this bleak scenario around. Tick-tock, tick-tock.

So, off I went to see first-hand the region of our planet currently flashing the loudest planetary climate fire alarm signal. A recent study by NOAA found that the Arctic is heating up twice as fast as the rest of the planet.

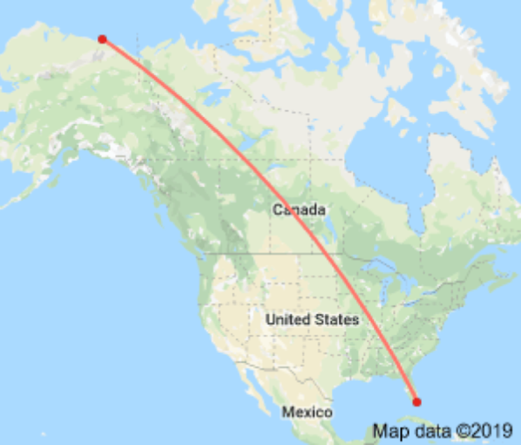

Distance from Key Biscayne to the Arctic village of Katovik, AK: 3,936-miles. Despite being far way, recent studies confirm that what happens in the Arctic can have significant impacts on Florida coastal communities like Key Biscayne.

As I began my 3,936-mile journey to the Arctic, I could not help but wonder what all the people I saw in the cavernous airports were thinking. Surely, if our best scientific minds were telling us that we were in a battle for our survival, everyone should be talking about this, but no one seemed alarmed. Why wasn’t the media talking about this 24/7 as it did when covering a war or other national emergency?

The answer to this query comes partly from the old adage where a frog, which is dropped into a pot of boiling water, quickly jumps out of the pot, but, if it’s placed in the pot with room-temperature water, which is then heated up slowly, the poor frog won’t notice the slow change as it meets its groggy death. In humans, this neurological glitch is called Change Blindness and helps explain part of the puzzle keeping humans from treating the climate crisis as an emergency; the other part of the puzzle being mostly political and corporate disinformation.

Aerial view of Brooks Range, AK which is part of the Alaska North Slope: a region of Alaska encompassed by the northern slope of the Brooks Range lying along the coast of two seas in the Arctic Ocean, the Chukchi Sea and the Beaufort Sea. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

As my small charter plane made its way over the mighty Brooks Range into the Arctic Circle, I looked down on the vast expanse of land that makes up America’s largest national wildlife refuge known as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) in Alaska’s North Slope Region, a pristine home to Arctic wildlife, including Polar Bears, Porcupine Caribou (whose migration is so large that it can be seen from space), Lynx, Muskox and innumerable bird species – a land, which until recently had been off limits to oil and gas development for decades, regardless of what political party was in control, especially as this is opposed by the majority of Americans. Today, the Battle for ANWR is viewed by many as the place where America’s Conservation Movement makes its last stand because opening up ANWR to oil and gas development would not only add fuel to a planet already on fire but also upend a land where native tribes and wildlife have coexisted for millennia.

My host, Kayotuk (left), an elder from the Iñupiat tribe in Kaktovik, AK. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

As the endless land beneath me – Alaska is bigger than Texas, California, and Montana combined – gave way to Earth’s northernmost body of water, the small single engine plane abruptly banked and began its decent to the dirt and gravel runway on Barter Island in the Arctic Ocean below. Upon landing, I was greeted by mild weather and deboarded the plane in a short sleeve shirt with a jacket tied around my waist; the first sign of climate anomalies taking place here. I was then handed my bags by the pilot and walked into the village of Kaktovik (pop.240) where I would be staying with Kayotuk, an elder from the Iñupiat tribe.

Kayotuk’s sister-in-law proudly shows me her winter food stock obtained from recent hunting activities. The Iñupiat of the North Slope of Alaska are heavily dependent on subsistence hunts of marine and land mammals, fish, and migratory birds. Nothing in the hunt goes to waste. Her winter stock included, among other things, Caribou heart and meat from seals and whales. Traditionally, the Iñupiat stored their meat in underground cellars in the permafrost underground. However, these natural ice cellars that generations of native Alaska communities have relied upon to store food are melting. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

It had been a long journey and, after getting briefly acquainted with my host, I quickly fell asleep until loud gunshots in the middle of the night suddenly awoke me. Kayotuk explained to me that, because of the danger posed by Polar Bears (Earth’s largest carnivores) to the villagers and their children, the village has set up 24 hour bear patrols, and the gunshots meant that bears had tried to enter the village and had either been scared off or shot. This was another sad consequence of a warming planet as the hungry Polar Bears are forced to remain on land longer due to the ocean surrounding Kaktovik taking much longer to freeze. Because Polar Bear prey is found on sea ice, the bears frequently wander into town in search of food while they wait for the sea ice to reach them. During my walks through town, I was deeply moved when I came upon the carcass of Polar Bear that had been sadly shot because of these tragic aberrations.

Polar Bear hide drying on the ground in Kaktovik, AK. Climate disruption forces hungry bears into town in search of food due to the ocean surrounding Kaktovik taking much longer to freeze. Bears that cannot be successfully scared away with gun shots are put down. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

While documenting Polar Bears and the remains of Bowhead Whale from a recent hunt by the Iñupiat tribe (the U.S. Govt. permits the tribe to hunt three Bowhead whales per year, and the discards help keep the climate-beleaguered bears alive) – a boat skipper informed me that despite it being October, the sea ice was still over 300 miles away, a record distance for this time of the year.

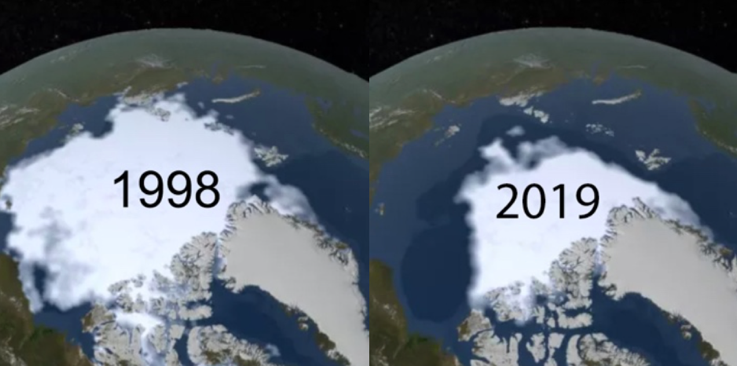

In the Arctic, sea ice reaches its yearly minimum during the month of September. The images compare September Arctic ice from 1998 and 2019. Data reveals, the Arctic is at its warmest for at least 4,000 years. (Source: NSIDC/NASA September ice.)

The data shows that sea ice in the Arctic has been retreating 12.9 percent per decade unleashing dire consequences not only for species like Polar Bears but also for the human species in the form of rising sea levels, ocean acidification, more extreme natural disaster, and climate change acceleration due to methane, a potent greenhouse gas 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at trapping atmospheric heat, being released from melting permafrost.

Polar Bears and their cubs increasingly have to wait longer periods of time on land due to a warming Arctic. This photo is from early October 2019, and the sea ice where Polar Bears find their prey is still over 300 miles away. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

Moreover, the Albedo Effect, which keeps Earth cooler as ice and snow reflect about 80% of the Sun’s energy back into space, enhances warming because, as ice and snow melt, the darker oceans and land absorb the heat causing more warming in an increasing cycle.

None of this bodes well for coastal Florida communities like Key Biscayne where sea level rise, due mostly to melting polar ice, is already speeding up.

Sunrise in the Arctic Ocean. Captain Ketil Raitan, vocal opponent of drilling in the Arctic, looks over the horizon searching for Polar Bears. In winter, he is a renowned dog musher, participating in the famous Iditarod Race with his son Martin. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

Despite all of this, many of the indigenous people in Kaktovik favor opening up their land to oil exploration as the riches being dangled in front of them by the oil majors are simply too hard to resist. The Mayor informed me that the community was split over the issue, and a previous village employee, Evelyn Reitan, told me that she had been fired from her post for what was perceived as her strong opposition to oil development in ANWR.

As the frozen ground (permafrost) underneath their homes melts and sea levels rise,

native Arctic communities like Kaktovik are increasingly at risk. Climate disruption threatens their homes, culture, and livelihood. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

Tribal communities like Kaktovik bare little blame in the global crimes against humanity being perpetrated by the oil majors, i.e., today, an increasing number of the public believes that climate crimes should be prosecuted in forums like the Hague, including payment of reparations for the environmental damages caused by climate disruption, especially if the evidence proves, as is being discovered, that many of the offending corporations were aware of the dire consequences of their actions and proceeded anyway.

Aurora borealis over the Arctic community of Kaktovik, AK. The wonders of the planet we are privileged to call home are far and wide. Will we allow Earth to continue to sustain us? Science indicates that time is running out. (Brian Rivera Uncapher via Key News)

Seeing the front lines of the climate crisis with my own eyes was bittersweet. Sweet because I was able to observe up close the proud, kind, and magnificent people and culture of this blessed land, in addition to having profoundly moving experiences like being awestruck in solitude with the Northern Lights above me and so close that I felt I could touch them as if entering another realm where the Spirit of the living Earth permeates every fiber of one’s being. And, bitter because the Earth was clearly showing me that we had not only harmed her but also harmed the living creatures which she is responsible for sustaining, including ourselves.

Contact

Info@ArcticWild.Org or Brian@ArcticWild.Org for information on Alaska Wildlife Photography Workshops and public lectures. Donations to the nonprofit may be placed online at ArcticWild.Org .

About the Author

Executive Director for ArticWild.Org , a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting wild Arctic environments. Brian received his Juris Doctor degree from the University of Miami School of Law in 1990 where he served as Editor-in-Chief of the law school’s Business Law Review. His course load and published work dealt with international law and diplomacy. Upon graduation, he founded a Fair-Trade company specializing in assisting Central American indigenous communities in getting their handicrafts to European markets, including setting up their relationships with the World Wildlife Fund in Holland, Germany and Scandinavia. Brian’s work has been recognized by the Fine Art Photography Awards, the International Photography Awards, Nature’s Best Photography, Landscape Photography Magazine as well as commented on by various other organizations, including the United Nation’s Biodiversity Initiative, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council, the Audubon Society, the American Bald Eagle Foundation, DIY Photography™, Photography Life™, and the Alaska Wilderness League. His Alaska bald eagle cinematography has been included most recently in the 2019 documentary, Rock Paper Fish, and his recent photograph of the skin patterns of an Iguana won the top award in the Art Wolfe Photography as Art Competition. He is a frequent contributor to magazines, trade journals, and industry blogs.

Brian’s photography and film work have allowed him to witness first-hand the key role the Arctic plays in safeguarding Earth’s unique atmosphere and led him to found ArcticWild.Org, a nonprofit organization specifically focused in protecting and preserving the wild Arctic. For additional information on Brian, please visit his website or contact Brian for information on his photography tours to Alaska.

Join the conversation